Travel Books: The Art Of Travel, Alain De Botton

Thank God for thrift stores! I am always amazed at the books I find that I didn’t even know I wanted to read. My latest thrift store find is “The Art Of Travel” by Alain de Botton. The format of the book is very interesting as de Botton links his travels to various places with writers, artists and thinkers (e.g. Flaubert, Wordsworth, Van Gogh and Edward Hopper) who lived or visited in the same places he writes about.

Each chapters links an artist with a place and a theme. The first chapter being about how the anticipation of travel is as important and interesting as travel itself. The place is Hammersmith, London and Barbados, with J.K. Huysmans as the artist guide.

Tom Thompson’s iconic painting of a The Jack Pine (1916-1917) tree has been the catalyst for Canadians to travel to northern Ontario to connect with nature for generations. (photo credit: National Gallery Canada).

Who is Alain de Botton?

He is a Swiss-born British philosopher with a focus on philosophy’s relevance to everyday life. He helped start the School of Life in London, UK in 2008 and has written several books including: “How Proust Can Change Your Life,” “The Pleasures and Sorrows of Work” and “The Architecture of Happiness.” He even has two TED Talks. Hmmm….these are all subjects that interest me. How did not know about this guy?

Link: TED Talk de Botton a kinder gentler philosophy of success

Link: TED Talk de Botton Atheism

The Art of Travel is a very interesting read, while the writing is more intellectual and the ideas and links more challenging than the typical, travel books that mostly descriptive. Despite this, is an easy read. Here are a few of the thought provoking ideas that resonated with me.

Country vs City!

I have always been puzzled by urban dwellers’ need to get away from the city and head to the country on weekends or for vacations. For me the city offers endless opportunities to explore nature as well as man-made places – but maybe that’s just me. In the chapter titled, “On the Country and the City,” the place is The Lake District (a mountainous region in north west England with the highest mountains and largest deepest lakes) and your guide is William Wordsworth.

de Botton traces the human need to travel to the country back to the second half of the 18th century, when city dwellers began, for the first time, to travel in great numbers to the countryside “in an attempt to restore health to their bodies and, more importantly, harmony to their souls.” He notes in 1700 only 17% of the population of England and Wales lived in a town, but by 1850, it was 50%. Interestingly, de Botton doesn’t say that today, 84% of England’s population is urban, a typical percentage for most of the developed world.

Interspersed with his countryside experiences, de Botton shares some of Wordsworth’s prose:

The cock is crowing

The stream is flowing

The small birds twitter,

The lake doth glitter…

There’s joy in the mountains;

There’s life in the fountains;

Small clouds are sailing,

Blue sky prevailing

de Botton illustrates how, for Wordsworth the landscape, (its streams, flowers, birds, trees) “was an indispensable corrective to the psychological damage inflicted by life in the city and a requirement for happiness.” For the poet, nature has the power to suggest certain values to us – oaks’ dignity, pines’ resolution, lakes’ calm – and, in unobtrusive ways may therefore act as inspiration to virtue.

Indeed, who hasn’t experienced the sense of humility when awed by the beauty and grandeur of nature when travelling? Indeed, most humans need a good dose of humility every once in awhile.

Wordsworth “accused cities of fostering a family life destroying emotions: anxiety about our position in the social hierarchy, envy at the success of others, pride and a desire to shine in the eyes of strangers. City-dwellers had no perspective, he alleged; they were in thrall to what was spoken of in the street or at the dinner table. However well provided for, they had a relentless desire for new things, which they did not genuinely lack and on which happiness did not depend. And in this crowded anxious sphere, it seemed harder than on an isolated homestead to begin sincere relationships with others.”

Wow…though written in the middle 1800s, is so true today!

Wordsworth said about his life in London, “how men lived even next-door neighbours, as we say, yet still strangers, and knowing not each other’s names.” Again, still true today, probably even moreso.

Later in the chapter, de Botton notes “Nature would, he proposed, dispose us to seek out in life and in each other, whate’er there is desirable and good. She was an image of reason that would temper the crooked impulses of urban life.” I began to wonder - does nature really have that big of an impact on human life?

de Botton goes on to say, “to accept Wordsworth’s argument requires we accept the principle that our identities are to a greater or lesser extent malleable; that we change according to whom – and sometimes what – we are with. The company of certain people excites our generosity and sensitivity, of others, our competitiveness and envy.”

I don’t think this is too hard of an argument to accept.

When reading this, It is important to remember cities and towns in the 1800s were much dirtier than they are today, the average home was not as large, nor had as many conveniences, and the work/live balance weighed much heavier on the side of work. Does this mean our need to experience nature is less today?

Perhaps the best statement in this chapter was the idea that “perhaps unhappiness can stem from having only one perspective to play with.” One of the great things about travelling, even exploring new communities in your city, is that it gives one a different perspective on our everyday life, which in turn, makes you think a bit differently about the world we share.

On Eye-Opening Art

In this chapter, de Botton looks at how visual art actually changes the way we see and experience the world around us and how it can influence where we travel to.

The author traces how Van Gogh discovered and dissected a different reality (from previous artists) to Provence, one that captures the beauty of cypress trees, the colour of the architecture and the labour of the people. He helps us see reality of place from multiple perspectives.

One example is the artist’s depiction of the movement of the cypress trees in the wind he painted in 1889. This painting captures the cone-like shape of the tree, with fonds that grow from a number of points, creating endless swirling lines that take on the appearance of a flame flickering in the wind. When de Botton purposely walked to a garden to see the cypress trees as painted by Van Gogh, he quickly realized he saw the trees in a way he had never seen before.

In Canada, how many of us have seen a tree and said it looks like Tom Thomson’s “The Jack Pine,” or been wandering an old growth forest in British Columbia and thought this forest looks like an Emily Carr painting?

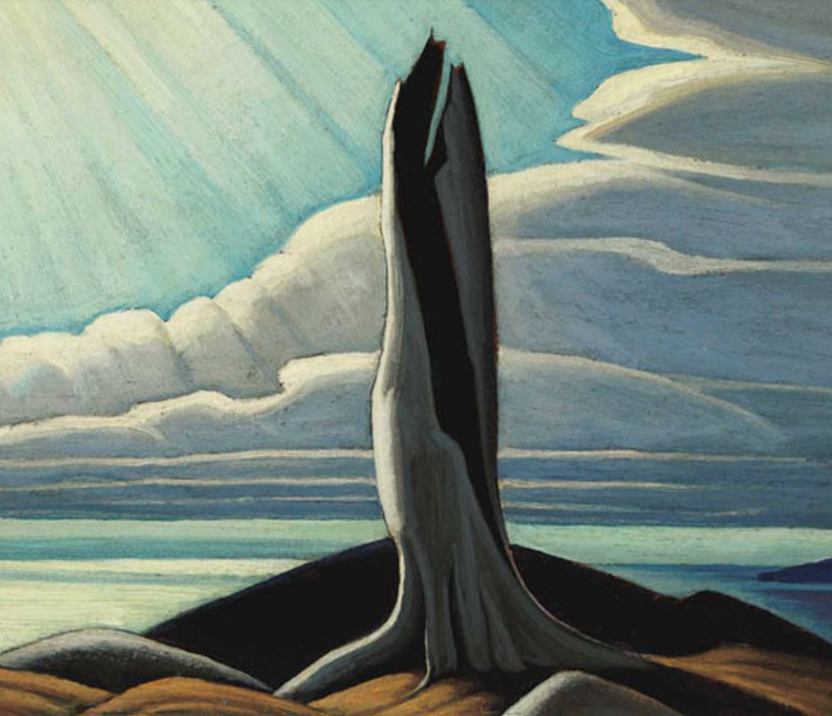

Or seen an old decaying tree stump and thought that looks like a Lawren Harris’ painting?

For many, of us our first impression of a place was from an artwork in an art gallery, museum or a book. At least that was the case until the proliferation of photography and social media.

In this same chapter, de Botton provides a very interesting discussion of reality in painting and how modern artists depict reality in different ways. He notes how Van Gogh wrote “the world is complex enough for two realistic pictures of the same place to look very different depending on an artist’s style and temperament. Every realistic picture represents a choice of which features of reality are given prominence; no painting ever captures the whole, as Nietzsche mockingly pointed out in bit of doggerel verse entitled The Realistic Painter.”

“Completely true to nature!” – what a lie

How could nature ever be constrained into a picture?

The smallest bit of nature is infinite!

And so he paints what he likes about it.

And what does he like? He likes what he can paint!

Provence wasn’t the only place the author was enticed to explore because of its portrayal in works of art. He once visited Germany’s industrial zones because of Wim Wender’s “Alice in the Cities.” The photographs of Andreas Gursky gave him a taste for the undersides of motorway bridges, while Patrick Keiller’s documentary “Robinson in Space” inspired him to holiday around the factories, shopping malls and business parks of southern England.

de Botton concludes with saying “we tend to seek out places once they have been painted and written about by artists. While art cannot single-handedly create enthusiasm for a place, it definitely contributes to it and guides us to be more conscious of things that we might have missed.”

In the last 1800s, Claude Monet created a spectacular garden next to his home in Giverny, France. As a result of his plethora of paintings of the garden his house and garden became a major tourist attraction for those interested in gardens, art, photography and painting.

de Botton uses Edward Hopper’s Compartment Car to illustrate how “few places are more conducive to internal conversations than a moving plane, ship or train. There is an almost quaint correlation between what is in front of our eyes and the thoughts we are able to have in our heads: large thoughts at times requiring large views, new thoughts new places. Introspective reflections which are liable to stall are helped along by the flow of the landscape.”

Last Word

“The Art of Traveling” is full of insightful observations by the author and others about how and why humans love to travel, and how travel links to the human psyche, our happiness and how we relate to one another.

I leave you with one last thought, which de Botton derives from reading the work of Xavier de Maistre's “Journey around My Bedroom,” published in 1790.

“The pleasure we derived from journeys is perhaps dependent more on the mindset with which we travel than on the destination we travel to. If only we could apply a travelling mindset to our own locales, we might find these places becoming no less interesting than the high mountain passes and butterfly-filled jungles of Humbolt’s South America.”

As we all struggle, some more so than others, with the changes placed on our lives due to COVID-19, we would all be well advised to adjust our mindset to see and seek the beauty around us, rather than lust after that in another place.

Everyday Tourist Tip: Young travelers, have you ever felt like your luggage is just another cube in a sea of things? --Custom Luggage Tags are the beacon of light on that ordinary box. You can customize your luggage tag with your favorite travel motto embossed on a simple leather label, paired with a small watercolor sketch of a Parisian cafe, and personal contact information. These are more than just tags, they’re carry-on souvenirs. They clearly say “this is mine” without being ostentatious, blending practicality with understated cool. Whether you’re a solo backpacker or a weekend getaway traveler, custom luggage tags will ensure your gear finds you.

If you like this blog, you will like these links:

Travel Books: Explore The World With Olferts

Importances of Books, Library & Reading During COVID

Jan Morris: Canada A country of prosaic cities!

Jan Morris: Edmonton A Six-Day Week?